🫁 Topics in Respiratory Physiology – The Alveolar Gas Equation in Clinical Practice: from the Oxygen Cascade to Bedside Decision-Making

By: BETINA SANTOS TOMAZ, FISIOTERAPEUTA - 02/09/2026 09:55

Continuing our series Topics in Respiratory Physiology, this topic proposes a deep dive into one of the most classical, and at the same time most neglected, pillars of respiratory physiology applied to the ICU: the Alveolar Gas Equation (AGE).

Building on a recent editorial published in Intensive Care Medicine by Professors Wongtirawit, Raimondi Cominesi, and Laurent Brochard, the text revisits the oxygen cascade, linking fundamental concepts, alveolar ventilation, gas exchange, perfusion, and metabolism, to the most common clinical pitfalls in the interpretation of hypoxemia.

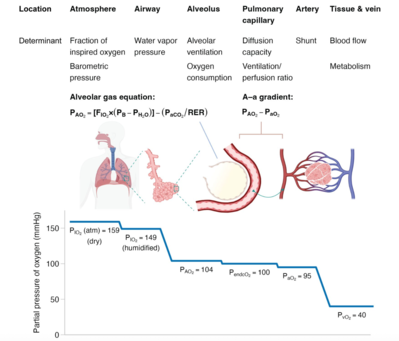

Figure 1. Oxygen cascade and the alveolar gas equation.

The figure illustrates the progressive decline in the partial pressure of oxygen (PO₂) from the atmosphere to peripheral tissues, a concept known as the oxygen cascade, as well as the physiological determinants involved at each step of this process.

In the atmosphere, PO₂ results from the product of barometric pressure (PB) and the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO₂). As air enters the airways, it becomes fully humidified, incorporating water vapor pressure (PH₂O), which reduces the inspired oxygen partial pressure (PIO₂).

Within the alveoli, alveolar oxygen pressure (PAO₂) is determined by two main processes:

(i) alveolar ventilation, which supplies oxygen, and

(ii) oxygen consumption, related to gas uptake into the blood.

These processes are integrated by the alveolar gas equation, in which the first term represents the oxygen tension of fully humidified inspired gas reaching the alveoli, while the second term incorporates arterial carbon dioxide pressure (PaCO₂) and the respiratory exchange ratio (RER), reflecting systemic oxygen uptake.

Beyond the alveoli, oxygen diffuses into the pulmonary capillaries, a step primarily influenced by the ventilation–perfusion (V/Q) relationship, frequently altered in critical illness, and, to a lesser extent, by pulmonary diffusion capacity. Oxygenated blood then mixes with venous return from physiological and pathological shunts, giving rise to the arterial oxygen pressure (PaO₂).

The difference between PAO₂ and PaO₂ defines the alveolar–arterial oxygen gradient (A–a gradient), an important indicator of abnormalities in gas exchange, including diffusion impairment, V/Q mismatch, or shunt.

Finally, oxygen is transported by the blood to peripheral tissues, where it is extracted for cellular metabolism, resulting in the mixed venous oxygen pressure (PvO₂).

________________________//________________________

More than simply revisiting a formula, the editorial highlights why the alveolar gas equation remains highly relevant in daily clinical practice, especially when dealing with:

hypoxemia due to hypoventilation versus gas exchange disorders;

correct interpretation of the alveolar–arterial (A–a) gradient;

the effects of PaCO₂, FiO₂, and barometric pressure on PaO₂;

advanced scenarios such as ECCO₂R, ECMO, low minute ventilation strategies, and situations in which traditional indices (such as PaO₂/FiO₂) may be misleading.

📌 Now we ask ourselves:

How often do we increase FiO₂ without first understanding which component of the equation is failing?

And how often is a “widened” A–a gradient merely a misinterpreted physiological artifact?

🎯 This topic is an invitation to reconnect classical physiology with real bedside decision-making, strengthening clinical reasoning and avoiding simplistic interpretations of oxygenation.

👉 Recommended reading (editorial underpinning this discussion):

Alveolar gas equation and its clinical implications – Intensive Care Medicine, 2026.

Shall we discuss? 🫁📊

To add an answer on this topic and read the replies...

You must have a valid and active xlung subscription

If you are already a subscriber, please Login at the top of the page, or subscribe now