Noninvasive ventilation for ARDS patients: can better interfaces make the difference?

Last update: Tuesday, 12 May 2020 at 14:23

The utilization of NIV for the ventilatory support in the treatment of patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) is a very controversial issue. The scientific literature on the efficacy of this technique in this context is very inconsistent. Nevertheless, an international epidemiological study involving 50 countries showed up to 15% of these patients are managed with NIV1 .

One of the main limitations of NIV in this clinical scenario is related to the frequent intolerance and low adherence of patients to the oronasal masks, usually the first choice for the interface. These individuals need the application of high airway pressures, especially PEEP levels above 10-12cmH2O for example. NIV intolerance may be related to air leaks and adverse events, making the technique inefficient in improving the oxygenation and the ventilatory pattern.

In this particular, the work of Patel et al published in JAMA deserves great attention2 . The authors from the University of Chicago, Department of Medicine, Section of Pulmonary and Critical Care, U.S.A., performed a randomized controlled study involving 83 patients with ARDS receiving NIV support by oronasal masks for at least 8h. After randomization, the patients either persisted in NIV with oronasal masks or they were switched to NIV with a latex-free Helmet 2 .

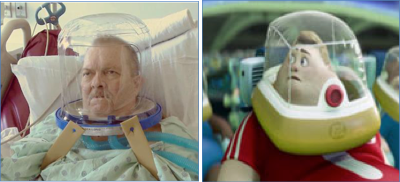

The Helmet interface has the advantage to applying NIV without touching the head and face of the patient. In fact, to illustrate it better is an interface very similar in design to the one presented in an imagined future in the Wall-E movie.

Helmet interface2 and the one showed int he Wall-E movie (Walt Disney Pictures/Pixar Animation Studios)

Patients randomized to the Helmet interface had a lower need for tracheal intubation (18.2% vs 61.5%, p < 0.01) and greater survival after 90 days (65.9% vs 43.6%, p = 0.02). The study was stopped both for efficacy and safety criterion due to a statistically significant effect favoring the Helmet interface and because another investigation demonstrated no efficacy of NIV delivered by oronasal masks in patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure2, 3 .

Various factors could have been responsible for the positive results associated with the Helmet interface. First of all, more tolerance and comfort with this interface in comparison with the oronasal mask must have been a key factor. Excessive air leaks are common with oronasal masks and are associated with adverse events, less comfort, patient-ventilator asynchrony, sleep deprivation and difficulties in setting high airway pressures 4 . In fact, with the Helmet interface higher PEEP levels were applied with lower driving pressures, making the protective ventilatory support more feasible during NIV. Lower driving pressures are associated with greater survival in ARDS patients5, 6 .

Before moving on with enthusiasm in indicating NIV trials with a Helmet interface as a routine approach do ARDS patients some considerations are necessary.

The Helmet interface still has some disadvantages. It requires specific settings on the mechanical ventilator as it has a very big internal volume that even may function as a dead space and can compromise the triggering and cycling functions of the ventilator. In fact, the majority of the ICU mechanical ventilators are not designed to work with a large interface such as the Helmet. Another drawback is related to the measurements of the tidal volume as they may become inaccurate while using the Helmet5 .

Another point of even greater concern is related to the possible deleterious effects of maintaining spontaneous respiratory muscle efforts during mechanical ventilation in ARDS patients, as others had shown beneficial effects of early controlled mechanical ventilation in the moderate and severe cases7 .

New investigations designed to confirm the promisor results obtained by Patel et al. are warranted before any recommendation in using this approach to deliver ventilatory support to ARDS patients be made. Furthermore, it is unknown if alternatives such as high-flow nasal oxygen therapy are comparable or even superior to the utilization of NIV with the Helmet interface. It is also worth to investigate if masks that do not touch the bridge of the nose and covers almost the entire face (total face mask type) could also de better options to patients with ARDS as the Helmet4 .

Total face mask with an adaptor for connection to an ICU double circuit ventilator allowing precise FIO2 titration up to 100% and monitoring of the tidal volume and other ventilatory parameters8 .

Above all, the work of Patel et al.2 . reinforces the importance of good practices in choosing, adapting, and harmonizing the interface both to the patient and to the mechanical ventilator

I would recommend very strict criterion to indicate and implement NIV to patients with ARDS, especially for the moderate and severe forms of the syndrome. When the decision to use NIV is made in these situations, a team with a good experience and expertise with the technique must be in charge of this task. In the case of signs of poor tolerance or inefficacy, prompt tracheal intubation should be done and protective ventilation applied early, as it is the most effective and safe ventilatory strategy based on the most recent evidence.

Author:

Marcelo Alcantara Holanda

- Associate Professor of Pulmonology and Critical Care of the Federal University of Ceará (UFC)

- Idealizer and founder of the xlung Teaching Plataform

References:

Comments